Deficits in joint mobility and/or stability could certainly impact individuals’ Functional Movement Screen (FMS) scores; however, it is also plausible that the movement patterns observed are influenced by the performers’ knowledge of the grading criteria. This study examined firefighters’ FMS scores before and immediately after being told what movement patterns were needed to receive a perfect score. This post provides a brief summary of the 2015 study conducted by Frost DM, Beach TAC, Callaghan JP, and McGill SM. FMS scores change with performers’ knowledge of the grading criteria – Are general whole-body movement screens capturing “dysfunction”? J Strength Cond Res 29(11): 3037-3044, 2015.

STUDY BACKGROUND

There are countless reasons why we move in a particular manner. Factors such as hip mobility, hamstring length, gluteal strength, perception of risk, prior experience, focus of attention, motivation, and simply being aware of the fact that movement matters can influence how we perform any given task. For this reason, assuming that any specific pattern is the product of “movement dysfunction” and in need of “corrective” exercise may be entirely unfounded.

The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) is a seven-task test that was developed as a low-cost means to “red-flag” potential problems that may predispose us to future injury. However, at present, there is no evidence to suggest that a particular FMS score accurately or reliably reflects the presence of movement “dysfunction”. Deficits in joint mobility and/or stability could certainly impact individuals’ FMS scores, but their scores may also be influenced by their awareness and appreciation for the criteria being used to grade performance.

STUDY DESIGN

Twenty-one firefighters (19 men, 2 women) were recruited to participate. All firefighters were free of musculoskeletal injury and pain at the time of testing and on full active duty. The study was designed to examine whether knowledge of the FMS grading criteria influenced FMS scores. Upon arriving for the testing session, the FMS was administered using published verbal instructions. No feedback was given, nor were the objectives of the screen described. Within 3 minutes of completing this initial test, participants were asked to perform the FMS a second time. However, this time they were provided with a verbal description of the criteria used to grade each of the seven screening tasks immediately prior to performing. The instructions provided were standardized across participants and no specific feedback was offered regarding any individual’s original FMS score. A research assistant blinded to the testing procedures graded the pre- and post-screens using video.

KEY FINDINGS

The firefighters’ mean (SD) FMS score increased significantly from 14.1 (1.8) to 16.7 (1.9) when they were provided with knowledge of the grading criteria. Significant improvements were also noted to four of the seven individual task scores (Deep Squat: 1.4 (0.7) to 2.0 (0.6); Hurdle Step: 2.1 (0.4) to 2.4 (0.5); In-line Lunge: 2.1 (0.4) to 2.7 (0.5); and Shoulder Mobility: 1.8 (0.8) to 2.4 (0.7)). With the exception of the Shoulder Mobility screen in which there is only one criterion, participants’ improvements could not be attributed to a single observation.

IMPLICATIONS

1. FMS scores may not reflect the absence/presence of movement “dysfunction”

Deficits in joint mobility and/or stability could certainly impact FMS scores; however, so too could performers’ perception of risk, prior experience, understanding of the task, focus of attention, motivation, and awareness of the grading criteria. The firefighters in this study improved their FMS scores within minutes of being told what movement patterns were required to achieve a perfect FMS score. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to assume that someone’s movement patterns are the direct result of a specific “dysfunction” or “impairment” that could be rectified via “corrective” exercise. Furthermore, a movement screen such as the FMS may lose its utility to evaluate the transfer of training or predict one’s risk of injury if the performers have knowledge of the tasks’ grading criteria. Whether or not the FMS becomes a viable means to predict future injury, the results of this study suggest that future efforts should not be directed to improve individuals’ performance on the test itself given that this objective could be accomplished artificially without actually impacting injury risk or athletic/occupational performance.

2. Our movement patterns are influenced by load, speed, etc.

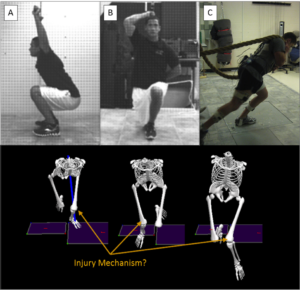

Movement is context dependent, which implies that attempts to predict how someone performs a high-demand (e.g. load, speed) sport-, occupation- or life-related activity with a low-demand screen could be prob lematic. This notion is illustrated in the figure. In addition to performing the FMS, the firefighters in this study were asked to perform two simulated job tasks. Despite receiving FMS scores of 16 and 20 on his pre- and post-feedback screens, respectively, the individual shown exhibited substantial frontal plane knee motion and a large frontal plane knee moment while advancing hose. Both of these measures are risk factors for ACL injury. The inclusion of higher demand tasks may not tell us exactly why the particular movement pattern was adopted, but they could help to establish more appropriate recommendations for training.